Francisco Chavajay Yojcom remembers having a feeling of apprehension every Tuesday and Thursday last year.

There was a monumental task before him but, as Unbound’s national coordinator for the Guatemala program, Chavajay squashed those feelings when standing before his staff. Despite the tediousness of the training and the time-consuming process laid out before them for how to implement a new methodology to help lift families and communities out of poverty — Chavajay witnessed in his staff an enthusiasm, commitment and dedication that was unshakeable.

They realized early on the potential of the methodology to activate the inherent potential that they knew already to be living inside of Unbound’s families in poverty.

“There was data in it we weren’t expecting that is helping us to reflect,” Chavajay said. “We found out families aren’t able to identify their own [most pressing] needs.”

The theory showed Chavajay and his staff that, while every family in the program has a level of poverty, the value of the methodology is in helping them to recognize it. Now going forward, Chavajay’s staff has created defined timelines and goals, based on the methodology, for helping families identify their individual poverty levels.

The Guatemala program’s revelations and modifications are no coincidence and are echoed across Unbound’s programs thus far, as staff came to realize during those early days the truth behind one member’s comment, “Who with a light gets lost?”

Light to Lead the Way

Unbound’s early days toward becoming the largest implementor of Poverty Stoplight methodology

August 10, 2022 | Be Informed

unbound meets poverty stoplight

Unbound believes the smartest path out of poverty is a self-directed one. To this end, Unbound partners with sponsored friends, helping them set their own goals and determine how to use their sponsorship funds to achieve those goals. Though goal orientation is an important aspect of Unbound, there have always been common and consistent challenges with goal orientation across Unbound programs.

For example, there is no global system to help families monitor their progress toward goal achievement, and aggregating data beyond the individual level is complicated. In addition, uncertainty persists around whether goals should be for the child or the family.

In 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic began to rage, Unbound’s international programs staff attended a virtual conference where they learned about an innovative tool that showed promise in helping the organization overcome some of the challenges of goal orientation. Martín Burt, author of the book “Who Owns Poverty?” and founder and CEO of Fundación Paraguaya, an organization dedicated to the elimination of poverty, gave a presentation that day on a new tool he had developed that he termed Poverty Stoplight.

Using a technology platform, Poverty Stoplight is both a self-assessment survey and an intervention model that enables people to develop practical solutions to overcome their specific challenges. At the core of the model is the concept that “families must be engaged as agents of change in their own poverty elimination strategy.”

“We thought this concept aligned with Unbound so much,” said Regional Project Director Becky Findley, who attended the virtual conference and is part of Unbound's Poverty Stoplight scale-up steering committee. “Even though we talk about sponsoring a child, we recognize that the child’s well-being is wrapped up in the well-being of the family as a whole.

“We know that poverty is multidimensional; this tool gives us a holistic assessment of a family’s situation and allows them to access that and create priorities while identifying a path to achieving their goals,” Findley concluded.

So, in 2021, Unbound initiated Unbound’s Goal Orientation powered by Poverty Stoplight, rolling out the new methodology as a pilot to four program sites and a total of 800 families to start. To date, Unbound has successfully implemented Poverty Stoplight globally to more than 19,000 of Unbound’s 285,000-plus families across 14 projects — putting Unbound on track to become the largest implementor of the Poverty Stoplight methodology worldwide thus far.

But to get there, Unbound program staff and sponsored families had a long road ahead.

Photo 1: Francisco Chavajay Yojcom, Unbound national coordinator for the Guatemala program, sits behind his desk in the Guatemala field office. From the few positive results his staff has already received from families who have taken the survey, he said he sees the Poverty Stoplight methodology being a necessary part of the program’s strategic plan going forward.

Photo 2: In the fall of 2021, one of Unbound’s Colombia programs launched their pilot of the Poverty Stoplight methodology to participating families, creating printed materials for the orientation that the families could easily digest. (Picture courtesy of program staff)

the true image of poverty

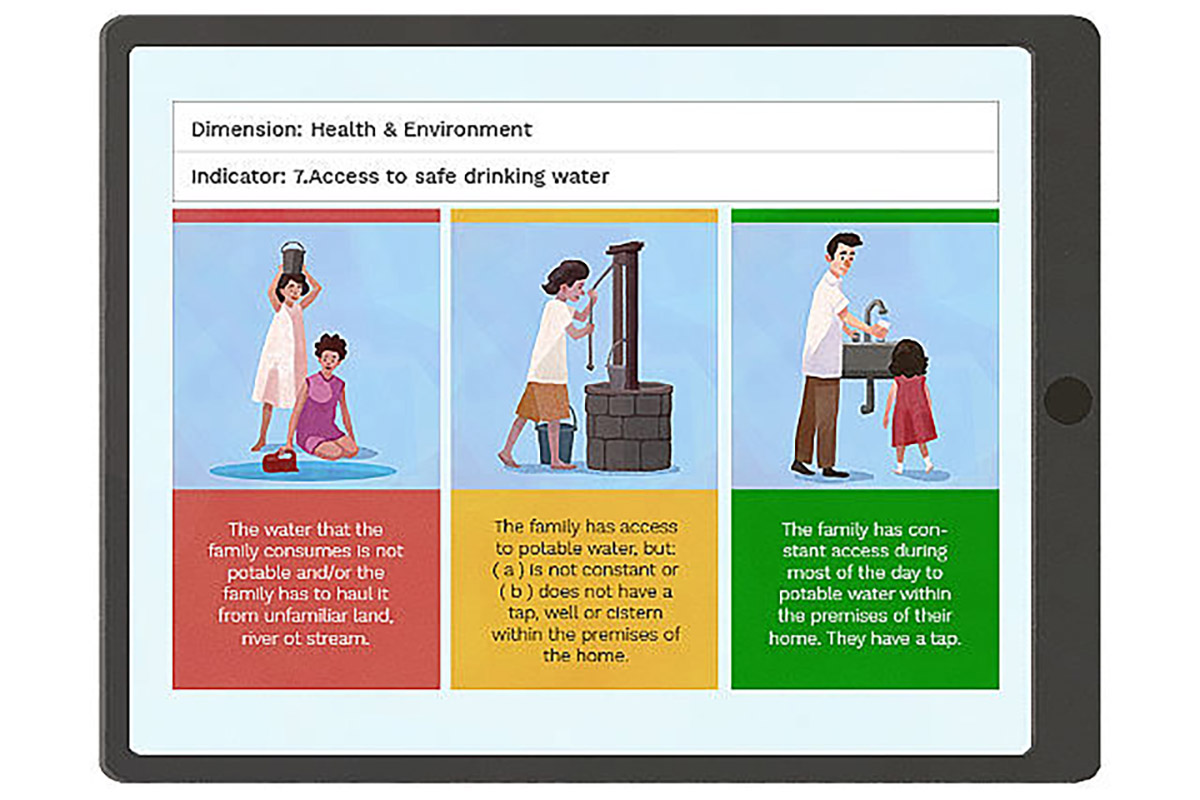

Poverty Stoplight puts the concept of poverty into visual form to define what it means “not to be poor” across six dimensions: Income and Employment, Health and Environment, Housing and Infrastructure, Education and Culture, Organization and Participation, and Interiority (or potential) and Motivation.

These dimensions are further divided into up to 50 community-specific indicators represented by three images and simple explanations that the family uses to complete a self-evaluated survey. Images in red describe “extreme poverty,” while images in yellow mean “poverty” and images in green are classified as “non-poverty.”

Using a computer or tablet, families choose a color that represents their situation. The results allow families to break down the overwhelming concept of poverty into manageable fragments and to develop their own “Life Map” to overcome poverty.

Unbound piloted Poverty Stoplight with four programs to start: Honduras, Meru (Kenya), Quezon (Philippines) and Cali (Colombia). The Guatemala program also signed on as an early adopter of the methodology.

Each of the programs received training from Fundación Paraguaya and Unbound, learned how to identify their community-related indicators with focus groups of sponsored families and piloted the surveys with 100-200 families, but it wasn’t as cut and dried as it sounds, and each of the programs met many implementation challenges along the way.

The staff orientation process takes two to three months to complete via webinars and multiple weekly meetings. The survey itself must be administered in-person to families and can take anywhere from 1 to 2 hours to complete. With limited amounts of tablets and staff to administer the surveys, onboarding at scale became and remains one of the greatest challenges for Unbound in implementing this effort.

In the Quezon program in the Philippines, staff also encountered concerns in pinning down the locations of families’ homes in rural areas where GPS signals were weak, as well as language barriers and safety concerns due to COVID-19. Despite this, Program Coordinator Marivic Ihap said the journey to actual survey implementation was worth the challenges.

“We were able to realize how to match the families’ priorities to their identified goals and the resources available in their families and from Unbound,” said Ihap, whose program will have implemented Poverty Stoplight to over 70% of the sponsored families they support by year-end. “For the families, they were able to see their strengths and weaknesses as a family in terms of poverty.”

Wanjiku Marius, Meru program coordinator, said her staff quickly learned from the early surveys that they did not know as much about the families and their situations as they thought they did.

“The data tells us that the families [in Meru] are not as extreme as we thought and, if given the chance, they can design their way out [of poverty],” Marius said.

The Guatemala program discovered interesting data in their initial surveys as well. According to Chavajay, they surveyed some families who recognized their weaknesses and chose appropriate indicators for red. However, some families would choose indicators that did not align with what staff thought they should have chosen.

Chavajay gave the example of a family living without a bathroom in their house. “How can it be that a family is not able to identify [this] as an urgent priority … that they are prioritizing other needs instead,” Chavajay said.

In another situation, in the Honduras program, staff witnessed families identifying trash disposal as a priority in their goals, a surprising issue staff had not previously recognized.

In Guatemala, Chavajay and his staff have been gratified to see the positive reactions of families even just in the initial phases of Poverty Stoplight, which he said gives families a sound plan for how to continue working toward their goals on their own in the absence of Unbound staff.

“Something beautiful about this method is that we make stairs, and each family understands a different level,” Chavajay said. “The important thing is that every family can take their step, climb their stairs, but to be able to go up, they must be aware of the level of the stairs on which they are — I think this is the strongest work that we have to do in the stoplight.”

Photo 1: Sponsored youth Clairgie and her parents complete the “My Goal Booklet” at the kitchen table in their home in the Philippines as part of Poverty Stoplight. Quezon program staff then walked them through how to complete the visual survey on a tablet.

Photo 2: Pictured is a screenshot of a portion of the Poverty Stoplight survey as it appears on mobile devices. Each image represents a situation that defines poverty in terms of red, yellow or green, and families choose the image that they think best represents their status. (Screenshot taken from povertystoplight.org)

Photo 3: An Unbound staff member helps a sponsored family member complete the Poverty Stoplight survey in one of the Colombia programs. (Photo courtesy of program staff)

the color of a goal

Though Unbound’s international programs staff believes it will be 2-3 years more before families' full progress toward goal achievement will be available from the Poverty Stoplight initiative, promising early follow-up observations are showing that sponsored families are learning just as much about poverty and goal orientation as Unbound’s own staff. Some are even already taking action to put themselves on a path to a better life “in the green.”

In Meru, hairdresser Jane, mother of sponsored child Grace, was surprised to learn after taking the survey that her family’s situation was not as dire as she had always thought.

“I thought I was below average, but I came to realize I am on average level,” Jane explained. “Now, I feel I have more confidence and motivation to put more effort into improving my standard of living.”

Before the survey, Jane thought she needed to work constantly to get ahead. However, the indicators from her survey helped her realize the importance of her own health and well-being, and that taking time for herself to relax would help her work more effectively in the long run. She is also prioritizing health care goals to ensure her family gets regular vision and dental check-ups.

Perhaps one of the most significant results of Poverty Stoplight thus far can be seen in the story of 16-year-old sponsored youth Verónica and her family from Guatemala.

Verónica’s family was chosen by the Guatemala program to be part of the initial testing phase of Poverty Stoplight. Verónica has seven siblings and her mother, María, sells homemade snacks in the streets of their community for income, while her father, Ramiro, works in construction.

After taking the Poverty Stoplight survey, the family decided to prioritize their goals around three of their indicators that were in red (extreme poverty): house and infrastructure, modern bathrooms and saving money. According to María, the family had always wanted to improve their home, the walls and ceiling of which were originally made of metal sheets, but they had never set a goal.

“The Stoplight has taught us that working together we will be able to accomplish our objectives,” María said.

With money they saved, the family has already begun building a new home. Ramiro and his older children work on the construction themselves on the weekends. The home will have four bedrooms and a dining room.

“Our main goal was the house and, thanks to God, we are doing it,” María said. “After finishing the house, we will start installing the shower and toilets … then we will go for the third goal, which is to save money. Together, we will be able to accomplish our goals.”

Photo 1: The current home of sponsored youth Verónica in Guatemala is made of wall-to-ceiling metal sheets and needed improvements.

Photo 2: After taking the Poverty Stoplight survey, Verónica’s family decided they needed to work as a team and prioritize making a better home for their family of 10. The family is working weekends to construct the four-bedroom home. Pictured, María, Verónica’s mother, gives a tour inside the foundation of their new home.

Photo 3: Verónica (back row, middle) stands inside the foundation of her family’s new home with her mother, María, and four of her younger siblings. Verónica is interested in studying business administration and tutors children in her village.

next step: scaling up

Unbound’s current long-term goal with Poverty Stoplight is to have the program rolled out to the organization’s more than 285,000 families by 2025. But scaling up the implementation has been challenging.

“With thousands of families in each project, we couldn’t work with every country at once,” Findley said. “This year, we’ve grouped programs together to go through orientation.”

Projects that were early adopters of Poverty Stoplight and already had local indicators adapted are also sharing their knowledge and tool kits with other programs in the orientation phase.

Another issue that might impact scaling is that Unbound is re-evaluating Poverty Stoplight's usefulness for sponsored members who do not live in a family unit (such as those in orphanages, etc.) and elders as the organization learns about possible limitations to applying the methodology.

Unbound is piloting multiple strategies to help with scaling up, including one that involves hiring graduates of the scholarship program on a temporary basis to conduct the surveys, and another that involves mobilizing Unbound’s networks of mothers group leaders to conduct the surveys.

“In the end, our hope is that [on the Unbound side] we learn a better way to assess what is the actual life cycle of our program,” Findley said. “How do we graduate not just children, but entire families from poverty? Will Poverty Stoplight help us do that?”

Nevertheless, throughout this change process, Unbound’s overarching goal and commitment to those in need is only strengthened and remains — to walk in solidarity, side-by-side with sponsored friends as they make a path out of poverty.

Something beautiful about [Poverty Stoplight] is that [it is like] making stairs, and each family understands a different level. Every family can take their step, climb their stairs, but to be able to go up, they must be aware of the level of the stairs [poverty] on which they are.

— Francisco Chavajay, Unbound National Coordinator for Guatemala